The science underpinning Ecosystemics is rock solid. The scientists whose works form the foundations for Ecosystemics are brilliant thinkers in diverse fields whose contributions have fed, inspired, and guided the rigorous scientific, mathematical, and technical methods we use in our work. If some of their names may not be familiar to you, we hope after learning more they will be forever memorable and trusted authorities you, too, can cite and learn from. We are certain they will be pivotal characters in the story we are writing: “How We All Solved the Multi-Crisis Working Together”.

For an example of how the science described here has profound practical implications, consider the opposite outcomes of seeking to solve environmental crises by way of the mechanistic paradigm compared to a living system paradigm.

During recent heatwaves and record temperature extremes in the U.S., one short-term disaster response measure involved helping people get to places with air conditioning. Related efforts focused on ensuring the power grid could handle increased energy demand driven by air conditioner use. We present below the science behind our core principle that industrial mechanistic systems are inherently unsustainable. In a heatwave, using air conditioning as a so-called “solution” actually makes the root cause of the heatwave worse. The causes of the heatwave, along with many related global environmental crises, is fossil energy use and associated greenhouse gas emissions. These in turn are driven by industrial culture, which itself is made possible by the prevailing mechanistic science paradigm. For an individual to temporarily reduce their own suffer by air conditioning is a case in which that individual may “win” or benefit today, but they and others will “lose” tomorrow due to worsening of global warming and extreme heat. These “solutions” are win/lose – short term isolated wins at the expense of loss long-term for all people and the planetary system as a whole. We don’t need more piecemeal “solutions” of this false kind – we need a whole new way of thinking, and a whole new science by which to understand the multi-crisis and develop novel, holistic, real solutions for these unprecedented times.

If the scientists we highlight next have been in any way “unsung heroes”, we are here to sing their praises loud and clear! We invite all to join in the chorus of voices singing about their brilliant insights. We also invite you to help us develop and implement practical solutions based on their foundational scientific and systems thinking works.

Robert Ulanowicz reveals the Life versus mechanism distinction seen in ecosystems

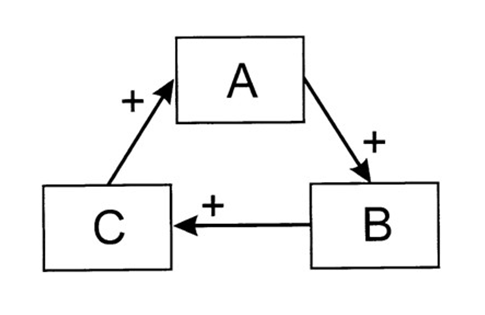

Robert “Bob” Ulanowicz demonstrated convincingly that ecosystems are non-mechanistic. He has studied ecosystems since 1972; his more than 200 publications in ecology, related sciences, and philosophy are listed here: https://people.clas.ufl.edu/ulan/publications/ One central method of his work is to study interacting processes in ecosystems. Familiar examples are pairwise interactions such as relationships between predator and prey, or mutualistic relationships such as those between symbiotic species like plants and microbial symbionts. A fundamental configuration Bob has studied is a three node (or component, or participant) network (or system) connected in a loop or cycle. He focused on the common ecological cases where all three individual interactions around the three-node loop are positive interactions – each participant in the network acts in ways that benefit the next participant. Because the system forms a circular loop, the positive interactions are passed forward and eventually back around to the first individual as a self-rewarding process. Ulanowicz emphasized the importance of the “indirect mutualism” exhibited in these networks. He also showed that the property of indirect mutualism can apply to networks/systems of any size (any number of nodes, components, or participants), and that such networks are present everywhere in nature – in all food webs, for example. Bob referred to these networks as autocatalytic.

Figure from Bob’s book, Ecology: The Ascendent Perspective (Fig. 3.1, 1997). A “hypothetical three-component autocatalytic cycle”. The + sign indicates the positive or beneficial relationship of one component to the next such as providing food.

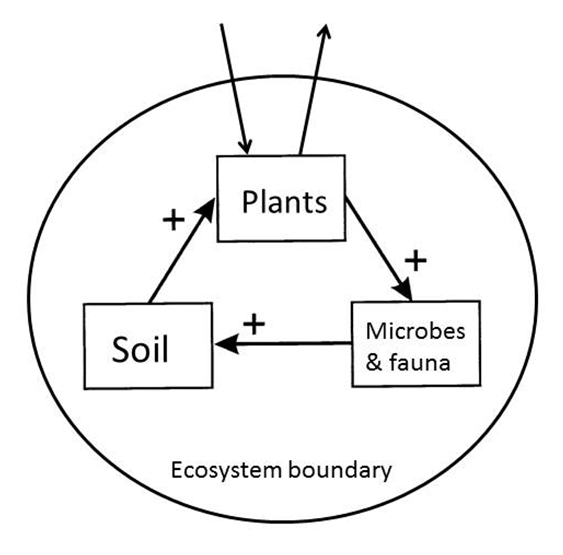

Figure borrowing from Bob’s archetypal 3-node autocatalytic cycle in Fiscus and Fath (Fig. 5.3, 2019) depicting a generic autocatalytic network common in feeding and nutrient relationships in terrestrial ecosystems. An important property of this system is how living systems improve essential environmental components such as soils. Improving their environments is an important non-mechanistic property of ecosystems. In contrast, all mechanisms degrade their own environments as they operate and function.

Bob’s PhD was in chemical engineering, and his first introduction to autocatalysis was in chemistry. After shifting his studies to ecosystems, he saw the clear difference in autocatalysis in the two realms:

“In EAP [his book, Ecology: The Ascendent Perspective] (Ulanowicz, 1997), Ulanowicz noted that autocatalytic systems are known and treated as mechanisms in chemistry, as all the reactants (similar to components as we have called them here) are fixed. The chemical reactants do not themselves change, and their modes and specifics of reaction (process) do not change, and so all dynamics and interactions are strictly determined and predictable—two signatures of mechanical behavior. But Ulanowicz stated that this is not the case in ecology and life science, where the participants or components can and do change, as they are more complex and adaptable. This makes all the difference, and Ulanowicz asserted that in the ecological case, the autocatalytic loop system is profoundly different—it is nonmechanical.” Fiscus and Fath (2019).

In the same book, Bob describes eight properties of autocatalytic cyclic networks, all of which are non-mechanistic (Ulanowicz, 1997). Find the citation for this important book, and the rest of Bob’s works, at the link to his publications above.

Bob’s work informs Ecosystemics’ founding strategy to focus on the scientific distinction between mechanisms and living systems.

He has given us the methods we need to clarify, demonstrate, explain why and how, and prove that mechanisms are not sustainable but living systems are.

Donella Meadows identifies paradigm change as highest leverage for system change

Donella Meadows was a revolutionary thought-leader in systems thinking and system modelling. She was the lead author of the best-selling groundbreaking book, Limits to Growth (1972), among many achievements. Her article “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System” (1999) inspires and informs the central multi-crisis solution and systemic change strategy of Ecosystemics.

She wrote:

“Folks who do systems analysis have a great belief in ‘leverage points.’ These are places within a complex system (a corporation, an economy, a living body, a city, an ecosystem) where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything. . . . We not only want to believe that there are leverage points, we want to know where they are and how to get our hands on them. Leverage points are points of power.”

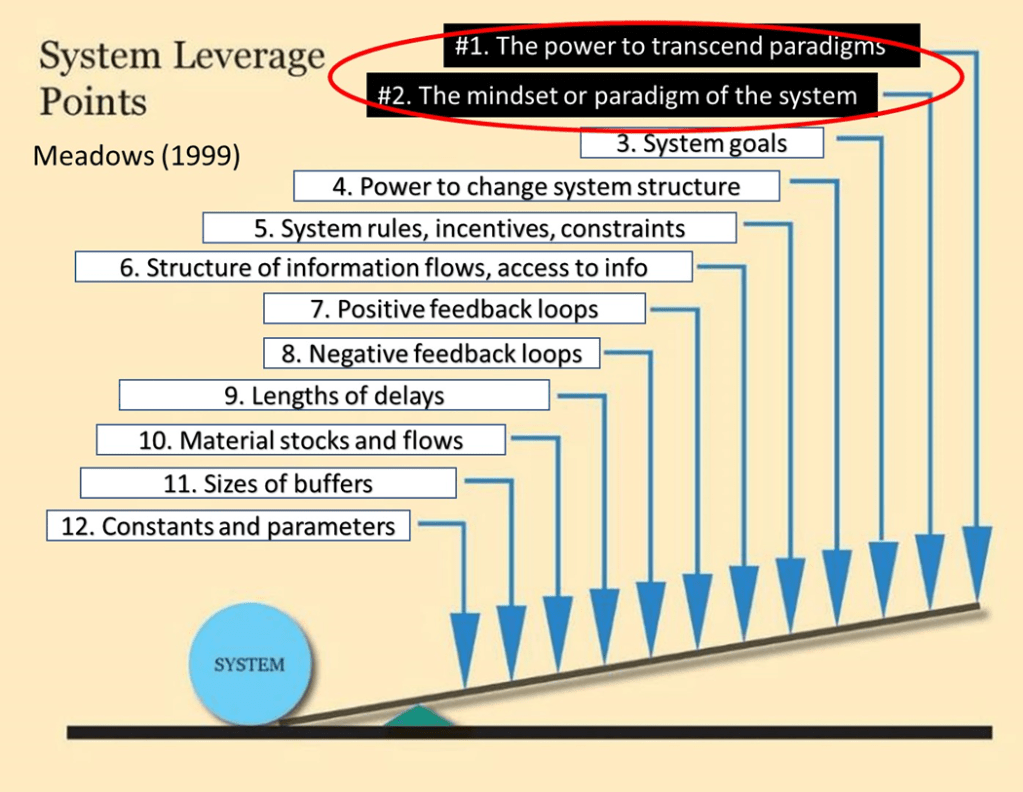

In her 1999 article on leverage points, she described 12 specific ones; ranked them in terms of their relative power, effectiveness, and leverage for system change; and described how they work as places to intervene, seek to influence, or guide complex human-environmental systems. Her top 12 list is:

PLACES TO INTERVENE IN A SYSTEM

(in increasing order of effectiveness)

12. Constants, parameters, numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards).

11. The sizes of buffers and other stabilizing stocks, relative to their flows.

10. The structure of material stocks and flows (such as transport networks, population age structures).

9. The lengths of delays, relative to the rate of system change.

8. The strength of negative feedback loops, relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against.

7. The gain around driving positive feedback loops.

6. The structure of information flows (who does and does not have access to information).

5. The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

4. The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

3. The goals of the system.

2. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

1. The power to transcend paradigms.

Figure of Meadows’ 12 leverage points for system change.

Having identified the paradigm as associated with the #1 and #2 sources of leverage, she explained why the paradigm is so powerful and suggested ways to change the paradigm of a social system. She wrote:

“The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions—unstated because they are unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them—constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.

Paradigms are the sources of systems. From them, from shared social agreements about the nature of reality, come system goals and information flows, feedbacks, stocks, flows and everything else about systems.

So how do you change paradigms? . . . In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep speaking louder and with assurance from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power.”

We in Ecosystemics focus on the paradigm of science as the source of highest leverage for change in industrial culture following the wisdom of Donella Meadows.

Her “think-do tank”, the adjacent and mutualistic systems science “thinking sustainability center” and co-housing and sustainable farm “doing sustainability center”, inspired our flagship project – the sustainable science facility.

Her article is online here, and more information on her life, work, writing, and legacy at the link below:

https://donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf https://donellameadows.org

Robert Rosen’s categorical distinction between Life and machine

Robert Rosen’s scientific and mathematical contributions provide core foundations for Ecosystemics. He studied the question, “What is Life?” over many years via multiple approaches. He wrote in eloquent terms of this profound and perennial question (Rosen, 1991) and how his published scientific work was:

“. . . driven by a need to understand what it is about organisms that confers upon them their magical characteristics, what it is that sets life apart from all other material phenomena in the universe. That is indeed the question of questions: What is life? What is it that enables living things, apparently so moist, fragile and evanescent, to persist while towering mountains dissolve into dust, and the very continents and oceans dance into oblivion and back? To frame this question requires an almost infinite audacity; to strive to answer it compels an equal humility.” (p. 11)

We share his curiosity about Life and the senses of awe, reverence, and humility with which he sought to understand Life. To his list of material phenomena less persistent than living systems we add industrial systems and machines; these additions are helpful as we seek to solve the global social-ecological multi-crisis.

Like Ecosystemics, Fiscus and Fath (2019) cited, borrowed, adapted, and employed multiple key insights and methods of Rosen including his metabolism-repair model of life; definition of life (organism) as “closed to efficient causation”; his study of the unique anticipatory nature of life; and his modeling relation as a general-purpose science approach, among many more. Perhaps the contribution with the greatest implication for solving the multi-crisis was his categorical distinction between Life and machine. These graphics and his quoted text will give a glimpse of his main idea. We highly recommend reading his books and articles to learn much more.

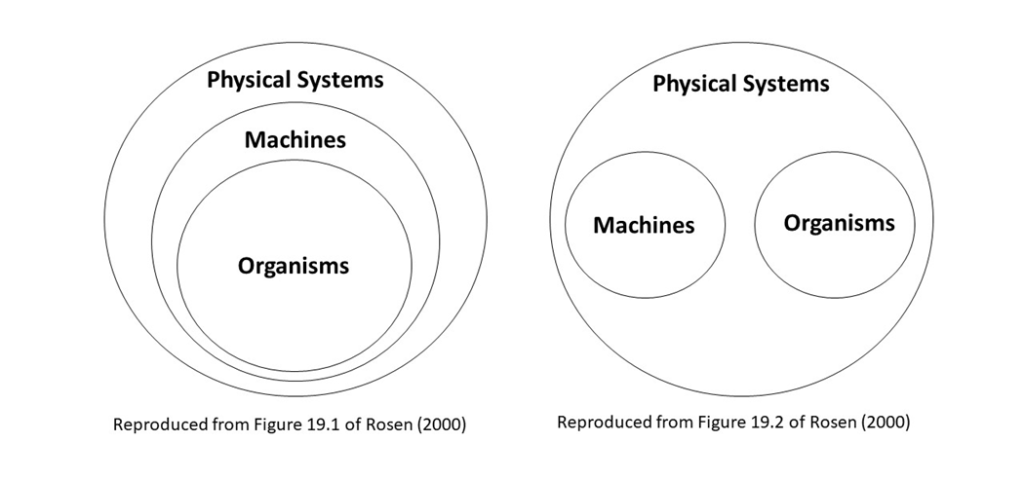

From Fiscus and Fath (2019, Fig. 5.3) adapted from Rosen (2000)

Rosen explained that the conventional science paradigm held the view in the left-side figure (his Figure 19.1) – that organisms are subsets of the more general category of machines (or mechanisms). He then described that a partial improvement in science came in the right-side figure (his Figure 19.2) with machines and organisms treated as different physical system types. However, his own view required another developmental step in conceptualizing these fundamental system categories.

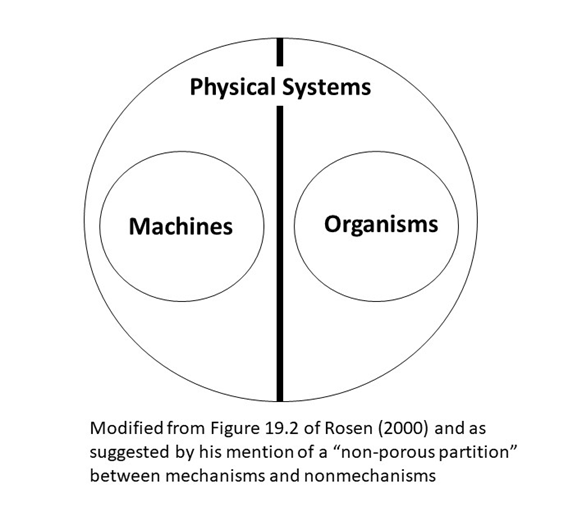

From Fiscus and Fath (2019, Fig. 5.4) created based on text by Rosen (2000)

Rosen did not publish this figure (Fiscus and Fath 2019, Fig. 5.4), but he did describe something like the solid impervious vertical bar we added between machines and organisms. He used information about complexity thresholds to make this point, and he referred to his work on types of mathematical and computational operations such as syntactic ones (Rosen, 2000):

“. . . I suggest a taxonomy for natural systems that is profoundly different from that of Figure 19.1 or Figure 19.2. The nature of science itself (and the character of technologies based on sciences) depends heavily on whether the world is like Figure 19.2 or like this new taxonomy.

In this new taxonomy there is a partition between mechanisms and nonmechanisms. Let us compare its complexity threshold with that of Figure 19.2. In Figure 19.2, the threshold is porous; it can be crossed from either direction, by simply repeating a single rote (syntactic) operation sufficiently often . . .

In the new taxonomy, on the other hand, the barrier between simple and complex is not porous; it cannot be crossed at all in the direction from simple to complex; even the opposite direction is difficult.” (p. 293)

We have taken Rosen’s groundbreaking work to heart and, with supporting work of Ulanowicz and others, agree with Rosen that “The nature of science itself (and the character of technologies based on sciences) depends heavily on whether the world is like Figure 19.2 or like this new taxonomy.” We extend his work and assert that the successful future of Life and humanity, and the outcomes of our confronting the multi-crisis, will likewise depend heavily on his “new taxonomy” in which mechanisms and Life are understood as categorically distinct. While not covered or quoted here, Rosen’s work includes formal mathematical proofs of his main ideas. To our knowledge, none of his science, math, or logic has ever been refuted.

To get a feel for how pervasive the scientific concepts Rosen studied are in everyday life, it helps to listen for the word “mechanism” in scientific publications, news and journalism, and everyday language. When you read or hear it, consider when “mechanism” is used as a metaphor and when it seems to refer to a literal mechanism.

It also helps to reflect on work by Robert Rosen and Bob Ulanowicz, who explained why “mechanism” is not even a valid metaphor, much less a literal system type, when referring to living systems.

These practices – perhaps similar to mindfulness developed in meditation practices – are ways to act on the recommendation of Donella Meadows for how to change paradigms. We are determined to “…keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm…” and “…keep speaking louder and with assurance from the new one…”

The “story of our times” contributed by others

In our debut informational document, we present an early draft of the story we seek to write – “How We All Solved the Multi-Crisis Working Together”. We see stories and narratives as powerful complements to science and action. The combination – science, story, and action – provides a variety of ways of knowing to facilitate learning together and acting together for systemic transformation. This effort to work with the story form has been inspired and aided by works of others. Here are a few of those.

The Great Turning

By Joanna Macy

“The Great Turning is a name for the essential adventure of our time: the shift from the Industrial Growth Society to a life-sustaining civilization.”

https://www.ecoliteracy.org/article/great-turning

The Third Story

By Human Energy, with emphasis on their work on the Noosphere

“The Third Story is a new attempt to envision a worldview that integrates the meaning, purpose, and ethical dimension of First Story logic [worldviews centered on mythic narrative and ritual enactment] with the universality, clarity of method, and applicability inherent in Second Story logic [worldviews thoroughly enmeshed in the natural sciences and modern technology].”

https://www.humanenergy.io/third-story

The Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead

By Paul Raskin, Tariq Banuri, Gilberto Gallopín, Pablo Gutman, Al Hammond, Robert Kates, Rob Swart of the Great Transition Initiative

“’Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead’ examines the possibilities for a sustainable and desirable world. The essay describes the historic roots, future perils, and alternative pathways for world development and advances the Great Transition path as the preferred route, identifying strategies, global actors, and values for a new agenda.”

https://greattransition.org/gt-essay

Here is another draft of a narrative explanation of the vision, mission, and strategy of Ecosystemics:

Our aim is to solve the global social-ecological multi-crisis that includes the climate crisis, increased species extinctions, toxic pollution, ocean acidification, and more. Our plan to do that starts with the information filters we use – the lenses shared by most people in industrial culture by which we focus and color the world.

We don’t usually think about our lenses and filters, but we always think with our lenses and filters.

What many in industrial culture don’t know is the lenses and filters with which we think are shaped heavily by science and economics. People living in indigenous cultures have very different lenses and filters by which they focus and color their world. People also may not know the lenses and filters with which we think have a huge impact on our behaviors, and these in turn have a huge impact on the environmental harms caused by industrial culture as a whole. We believe that solving the multi-crisis starts with our mental lenses and filters. We focus on learning how to change our filters and how our mental filters change the world. From that start, all else can follow.

Indigenous peoples (like “Sustainers”) and space exploration people (like “Transcenders”) – two complementary futures

Our priority focus in Ecosystemics is sustainability – solving the current multi-crisis to achieve truly sustainable and truly just culture and society on Earth. We also have developed an important parallel complementary work thread that seeks to resolve conflicts between:

- Movements and efforts for sustainability within the boundaries and limits of Earth and

- Movements and efforts seemingly for the exact opposite – for transcending the boundaries and limits of Earth by venturing into space.

Fiscus and Fath (2019) described two hypothetical cultural types to help explain one of the central conflicts and confusions of our times. We wrote about two hypothetical groups of people, the “Sustainers” and the “Transcenders”:

“This typology starts by assuming that everyone is aware of the environmental limits, constraints, and challenges now increasingly apparent, at least at some general level. However, the proposal is to see two different responses to this awareness. These two groups we label as ‘Sustainers’ and ‘Transcenders’, in order to make the typology value-neutral similar to Myers-Briggs personality types. We are not trying to say that either is ‘good’ or ‘bad’, or that one is better than the other in an absolute sense.

In this typology, the ‘Transcenders’ are aware of environmental limitations (again, even if just at some general level such as ‘human impacts are damaging the environment’, or ‘we are starting to see real shortages of key natural resources’), but when confronted with a perceived limitation they seek to break through it, innovate out of it, or change the world to transcend that external barrier or limitation. The ‘Sustainers’ adopt the opposite approach, and they accept the perceived environmental limit and then seek to change themselves to fit within, and sustain a lifestyle and culture within, that perceived real world constraint.”

We go on to say that the way of the Transcenders is aligned with a natural, fundamental, and essential aspect of Life including human life related to dispersal, migration, and exploration. We also suggest that the mainstream paradigm of reductionist, objectivity-focused, analytical, mechanistic (ROAM) science is appropriate for, and fully required for, the ultimate adventure of Transcender culture – the project to extend Life beyond Earth.

This working model for two cultural types gives the basis for describing a possible win-win relationship between two seemingly opposite worldviews, sciences, technologies, and cultures.

It provides the basis for seeing the best of ROAM science as valuable and worth preserving while also showing that Holistic Organic Living System science must be employed for Sustainer culture to succeed.

If this approach to link success of sustainability to success of space exploration seems a bit “far out” or far-fetched, consider some of the questions and issues that come into focus by entertaining a harmonious cooperation between the two camps. With this hypothetical typology in mind, we can ask meaningfully:

a. Should the Transcender folks agree to pause their mission and operations until we get the multi-crisis solved on Earth? It will be familiar to space enthusiasts that stabilizing life support systems on “spaceship Earth” is a clear priority for an essential mission.

b. Should the fossil energy sources be split 50/50 for the two cultures? Or should all the fossil energy be allocated to the Transcenders, since the Sustainers won’t need them over the long term anyway?

To search for true ecological complementarity, much like plants and animals, it is worth exploring a future in which these two groups work together and both groups, as well as Life as a whole, can succeed.

Works cited

Fiscus, D. and B. Fath. 2019. Foundations for Sustainability: A Coherent Framework of Life-Environment Relations. Elsevier / Academic Press.

Meadows, D., 1999. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. Sustainability Institute. Hartland, VT, USA. Available from: https://donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf

Rosen, R., 1991. Life Itself: A Comprehensive Inquiry into the Nature, Origin, and Fabrication of Life. Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 285 pp. ISBN: 9780231075657.

Rosen, R. 2000. Essays on Life Itself. Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 416 pp. ISBN: 9780231105118.

Ulanowicz, R.E. 1997. Ecology: The Ascendent Perspective. Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 201 pp. ISBN: 9780231108294.

Banner image of roots from Weaver, John. 1919. The Ecological Relations of Roots.

https://archive.org/details/ecologicalrelati00weav/page/n152/mode/1up?view=theater

Questions or Suggestions? Dig Deeper Still!

You can send us a message below to get in touch. We’ll reply quick as a wink 😉